This article provides a brief overview of some aspects of the Sunrise School project, including the Australian educational computing context in which the project emerged, the contribution and motivations of the institutions involved in its development, the international 'constructionist' movement it intersected with, its operation and closure, and finally, its legacy and impact. The article draws upon material held in the Sunrise Collection at the Melbourne Museum, institutional archives held by the Museum and the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), and a range of secondary sources.

The development of educational computing in Australia

Although university computing courses had been established in Australia in the 1950s, it was not until the late 1960s and early 1970s that schools began any form of engagement with computers. Through 1970s, school computing was largely ad hoc, and very limited in size and scope. Much of it was driven by mathematics departments or individual teachers who were interested in programming. Given the cost, size, and availability of computers at this time, school computing activity almost exclusively relied upon remote terminal access to mainframe or minicomputers held by higher education institutions. One of the most notable 'remote' school computing initiatives that took place was the 'Logo Turtle' program in Tasmania.

The 'Logo Turtle' program was an elaborate undertaking and a testament to the leading role that the education authorities in Australia's smaller States of Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia, played in developing a more coordinated approach to educational computing. The initiative based in Tasmania made use of Logo, the world's first computer programming language specifically designed as an education tool to be used by children. Logo (a cut-down version of the language Lisp) had been developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and technology research company Bolt, Beranek, and Newman in the late-1960s. In 1975, Australia's first copy of Logo was imported by Tasmanian teacher Scott Brownell and installed on the Tasmanian Education Department's minicomputer. A young teacher with some computer science experience, Sandra Wills, was then hired to demonstrate its use in Tasmanian schools. She did so by visiting schools with a programmable Turtle robot (an important Logo learning aid developed by MIT and later effectively 'replicated' by a Tasmanian engineer), along with a modem and terminal through which Logo on the Department's minicomputer was accessed to drive the robot.

In the late 1970s, the advent and diffusion of smaller and much cheaper desktop microcomputers rapidly opened up the possibilities for household and school computing. These computers began to appear in Australian schools in the early 1980s, and the education departments in the larger States began to catch up with the smaller States in terms of coordinating a more systematic development of computer education.

For schools, 1983 proved to be the watershed. In that year the Commonwealth Schools Commission argued that "a program of computer education in all Australian schools was of vital importance to Australia's future" and recommended a national program be funded by the Commonwealth. Although the level of funding fell short of that recommended by the Commission, it was still substantial and the rollout of computers into Australian schools quickly gained pace. While the Commission found that most secondary and some primary schools had acquired at least one computer by 1983, in the few years following many secondary schools had computer laboratories.

It is perhaps not surprising that though this period there was growing interest in examining the impact that this new technology was having on schools. In 1987, the Australian Council for Educational Research decided to take on this task.

ACER, school computing and constructionism

ACER, established in 1930, is one of Australia's most experienced educational research institutions with a particularly strong reputation for standardised testing and evaluation studies. In the mid-1980s, it had reviewed how it would structure its research activity. It determined that, in consultation with government and other stakeholders, it would identify a series of themes as a focus of its activity over 3-year terms. With computers now a feature of many Australian schools, one of the five themes it selected to pursue in its first 3-year term (1987-1990) was Education and Technology.

Liddy Nevile was appointed by ACER to head up the Education and Technology research theme. Nevile was a well-known figure in Australian educational computing. She had used computers in education since the 1970s, been involved in coordinating a range of activities with the Computer Education Group of Victoria (CEGV), had published several Logo student textbooks and teaching guides, and was well connected with a number of international leaders in the field based at MIT, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and beyond with whom shared her progressive beliefs around the power of computers to generate significant change to educational practice.

The original Education and Technology brief called for an evaluation of how computers were being used in classrooms; an approach that clearly aligned with ACER's past practice. But Nevile argued it was too soon and perhaps unhelpful to conduct an evaluation of school computing practices. The concern was that, given their infancy, such practices were unlikely to constitute the full range of educational possibilities computers could enable, and if 'best practice' was selected from among them this could close off avenues for exploring more effective and perhaps challenging alternatives. This line of argument was one that her progressive international colleagues were also taking into a lively debate on the impact of school computing. Nevile and her colleagues thought that the introduction of computers into schools had generally been rather conservative, in that they were simply being integrated into conventional educational practices, for instance 'standing in' for a teacher in delivering content and testing student knowledge in the case of Computer Assisted Instruction, or being used as a substitute for existing technologies like the calculator or typewriter. While there was value in these adaptations, Nevile and her colleagues were convinced that the computer could facilitate much greater change if given the chance. She convinced ACER that the Education and Technology brief should be reframed to provide such a chance.

Instead of an evaluation, the Education and Technology theme would explore the ways that computers could be used to facilitate new types of learning and hopefully provide a glimpse into what the future of schooling could be. This optimistic and exploratory approach was one that Nevile's progressive international colleagues, particularly the educationalist, mathematician and computer scientist Seymour Papert, his team at MIT, and leaders in the field in the UK such as Richard Noss, Celia Hoyles, and others were pushing.

Since the mid-1960s, MIT has been a leader of innovation in educational computing. Much of this was centred on the work of Seymour Papert, Marvin Minsky, Steve Ocko, Sylvia Weir and many others. Papert had joined the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab in 1963 after working with renowned Swiss philosopher Jean Piaget, a pioneer of constructivism, a revolutionary theory that redefined learning as an active process in which people construct new knowledge in their own minds as they reflect upon their interactions with the world and not, as previously thought, a largely passive process of simply receiving ideas. It was a theory offered profound consequences for educational design, pointing to the need for a shift away from the dominant school teaching mode of direct instruction and towards learner-centred methods that supported students to engage in self-directed, hands-on, inquiry and problem-based activities.

At MIT, Papert encountered a revolution in computing technology and set about connecting this to the revolutionary educational ideas of constructivism he had brought with him. Two key outcomes of this connection were the development of the Logo programming language that could be used by children to engage in the types of experiential learning central to constructivism, and Papert's realisation that learners 'construct' knowledge most effectively when their active engagement with the world is focussed on constructing things that are meaningful to them, an extension to constructivism that he called constructionism. Logo provided an (artificial) 'environment' in which to pursue constructionism enabling students to create 'microworlds' - exploratory environments where they could play and construct things and in doing so engage in meaningful challenges to their current thinking. The aim was to generate a rich learning environment, not unlike a sandpit for young children, which could provide endless learning and interest. The continuing development of one such environment (Scratch) engages millions of children worldwide today.

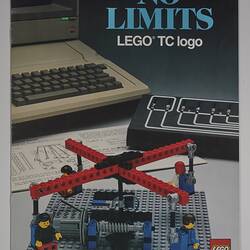

Since launching Logo in the mid-1960s, Papert and others had undertaken a large number of school-based initiatives to trial the use of Logo and application of constructionism in the classroom. In 1985, the MIT Media Lab began a School of the Future project at a Boston elementary school. The school was provided a large number of computers, Logo software and Lego/Logo Technic Control sets in a bid to build a learning environment in which a culture of using computers was embedded into everyday activity and to understand the impact of doing so.

ACER decided to create its own School of the Future, but do so outside of a formal school environment, and in doing so become the first substantial elaboration of the concepts of constructionist learning in an informal space. It was argued that an informal setting would help break students and teachers out of the conventional culture of school-based teacher-focussed activity and provide them greater autonomy to explore new forms of teaching and learning. The museum was purposefully selected as the informal site in which to create the technology-rich learning environment, since it would also provide teachers and students access to a vast array of cultural material to draw upon. Given the challenge to the future of schooling in the context of an emerging information era, some also saw the museum as a potential successor to the school.

Enter the museum!

When ACER approached the Museum of Victoria with a proposal to collaborate in the formation of a School of the Future centred on computers and robotics in 1987, the timing could not have been better.

In July 1983, the Victorian state government had formed the Museum of Victoria by amalgamating the National Museum of Victoria and the Science Museum of Victoria. The Museum of Victoria that emerged over the next few years had a much wider brief than its predecessors. This included promoting general scientific and technological awareness and helping the community to understand the social and economic implications and opportunities arising from technological change. This objective, and the Museum's strategic thinking around how it might be achieved, came into sharp focus after an independent museum inquiry released in late 1986 suggested the organisation set up an applied science and technology museum at a site in Spotswood. ACER had approached the museum at the very time a vision for such an applied science and technology museum was being developed. ACER's proposal got significant traction as a way this museum, which would come to be known as Scienceworks, could showcase 'high technology education'. So much so, that the School of the Future was one of the three original pillars in the proposal used by the Director of the Museum of Victoria to lobby the State Government to enable it to create Scienceworks.

At the end of 1987, ACER and the museum reached a verbal agreement to collaborate in establishing the school, now renamed the Sunrise School, on the Museum's Russell Street site. The museum was asked to provide a range of support, including the space for the 'classroom', access to the museum collection, and to help promote the school and its activities.

With the museum partnership now secured, ACER set about recruiting a school to provide participants for the project. In 1987, they approached Princes Hill Secondary College (Princes Hill) and after some deliberation they became the third core player in the project.

Participants from Princes Hill

Since the 1970s, Princes Hill had developed a reputation for its progressive and innovative practices in a range of areas, that included curriculum design, school decision-making, and behavioral management. The school was also considered an early adopter and leader in educational computing. It first engaged students in computing through remote access to the University of Melbourne mainframe and then, in the early 1980s, got its own computers - a set of 10 networked BBC microcomputers. The school engaged in several innovative computing projects before its involvement with the Sunrise School, including the development of a digital database of local historical materials in 1985. Princes Hill staff were also active contributors to COM3 (the CEGV journal) and Australian computing curriculum conferences. Given its commitment to innovation and educational computing, it is not surprising that Princes Hill took up the opportunity to be part of the Sunrise School.

The school agreed that from the start of the 1988 school year it would provide some teaching staff and a class of students as participants and research subjects to be engaged over a 3-year period. The participants would attend the School two afternoons per week. The class selected, Year 8B, consisted of 24 students. In the first year, two Princes Hill mathematics and science teachers, Queenie Aitkenhead and Margaret Fallshaw, were selected to deliver the Sunrise School program. In 1989, they were also joined by David Williams, another mathematics and science teacher who brought students from a second class into the program on an ad hoc basis.

The Sunrise School in action

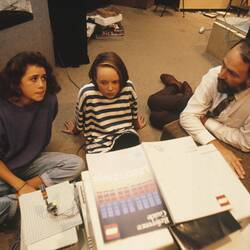

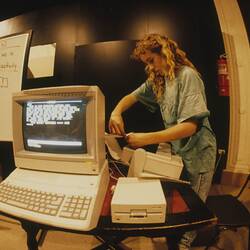

The Sunrise School opened in the North Rotunda of the museum in February 1988. It was an exciting, but somewhat challenging beginning, which is perhaps not surprising given the innovative and ambitious nature of the undertaking. When the Princes Hill students arrived, they found a classroom space that was somewhat chaotically 'embedded' in the museum collection (nestled around the Phar Lap exhibit), and there was no furniture, so they sat on the floor and fashioned 'computer tables' out of the boxes the computers came in. The teachers and students were now sharing an unfamiliar and less structured environment than they were used to and they were being asked to explore new ways to engage with each other in the teaching and learning process. There was also no set curriculum, given the desire to empower students to engage in self-directed learning. This was a very new experience for teachers and quite early on they felt some students might not have the skills to immediately engage in this type of learning and considered introducing some more structured skill-based activities.

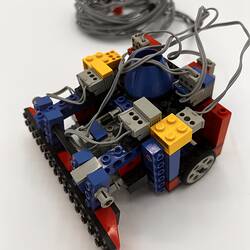

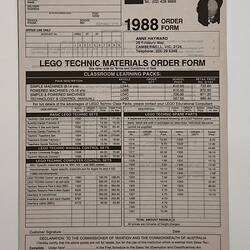

Despite these early challenges, and many more that would appear over the course of the project, the Sunrise School had delivered the tools for students to engage in self-directed, independent or collaborative creative projects. The classroom had ten new Apple IIE microcomputers loaded with LogoWriter and six sets of LEGO/Logo Technic Control robotics equipment that enabled students to build objects and vehicles they could control via the computers. These two technologies alone could support textual, graphic, robotic, musical, and animation work in an integrated way. In theory, the students also had some access to the vast collection of cultural objects in the museum and books in the State Library, but this often proved difficult in practice.

Through the first two years of the school's operation (1988 and 1989), the Princes Hill students and their teachers attended the Sunrise School two afternoons per week. The students, who tended to work in small groups, were encouraged by the teachers to identify and pursue projects that interested them and would result in the construction of meaningful outputs. These projects varied considerably, although most made use of the computers and robotics equipment. Some of the outputs students produced using Logo programming included a model of the variability in the time it takes for the sun to cross the sky in the summer and winter, a simulated stock market board, quizzes, illustrated stories, moving pictures and cartoons, adventure games and mazes, music, an 'intelligent' computer to simulate conversation, and a graphic simulation of a billiards game. The students also made extensive use of the programming capabilities of the LEGO/Logo robotics kits to produce computer-controlled cars, cable cars, a washing machine, traffic lights for controlling intersections, a programmable sign-writer, two, four and six-legged walking machines and robots, and a merry-go-round. As students engaged in these construction projects the teachers provided guidance and often asked them to reflect on their actions and articulate their problem-solving thought processes as a means of gauging the types of knowledge that was being constructed. (Some of the outputs created at the Sunrise School and video and audio recordings of the students producing them and teacher-student interactions can be seen in the Sunrise Collection at the Melbourne Museum.)

In 1989, as the end of the second year of operations approached, almost all parties seemed to have some reservations about the school's continuation into a third year. A number of logistical issues had arisen between ACER and the Museum over the course of the project that were not always resolved satisfactorily. This included access to space, furniture, and the museum collection. But there were also higher-level institutional concerns. Indeed, the two organisations never managed to actually formalise a satisfactory written agreement between them before ACER officially terminated their 'arrangement' at the end of 1989.

The Sunrise School had perhaps also run its course as an ACER research site at this point. While a significant amount of data had been collected at the school, there were no resources available to generate research outputs from this material. That is not to diminish the school's impact. Indeed, at this time, Nevile and ACER were heavily engaged in developing two other Sunrise Centres (described below) and many visitors to the school had witnessed first-hand how computers could be used to engage students in empowering and effective forms of learning.

It was Princes Hill that would effectively bring an end to the Sunrise School. While the teachers had been finding the program taxing and difficult, it was the students that took the initiative that ended the project. They banded together and arranged a meeting at Princes Hill where they withdrew their participation from the project. Amongst the students there had been growing dissatisfaction with the program. Concerns ranged from losing their lunchtimes when they were being transported to the museum, to worry about whether they would be behind when they re-entered the standard curriculum in later years. There also seemed to be some recognition that self-directed learning was hard work and after two years even some of the students who were initially enthusiastic were losing interest.

Impact and Legacy

Although the Sunrise School was not without its issues and consequently closed before the end of its planned three-year cycle, this audacious demonstration project had a significant impact on educational computing in Australia and internationally.

There is clear evidence that the Sunrise School generated important dialogue within and beyond the Australian education sector around the role computers could play in educational reform and attracted the world's leading educational computing experts from many countries to come to Australia and contribute to that dialogue.

The school also preceded other Sunrise Centres - the MLC Sunrise Centre in Victoria, the Queensland Sunrise Centre based at Coombabah State Primary School, the Batlow Sunrise Centre in NSW and Sunrise@RMIT at RMIT University in Melbourne. The establishment of these centres extended the exploratory work into both public and private school settings, and across all ages, and generated important research outcomes, informed developments in state-wide educational computing policy, and led to the development of the world's first laptop classes.

Where to from here?

This article is really just the tip of the iceberg. If you are intrigued by the Sunrise School and want to know more, the Sunrise Collection at the Melbourne Museum contains a range of items related to the school's activities. Melbourne Museum, ACER and MLC also have archives that contain important primary documents relating to Sunrise. A number of research reports have been written about the Sunrise Centres and there is a vast array of other literature that contextualises the project. A selection of these are included below.

References

Context: Educational Computing in Australia and Victoria

Johnstone, B. (2003). Never mind the laptops: Kids, computers and the transformation of learning. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse.

Jones, A., McDougall, A. & Murnane, J. (2004). What did we think we were doing? In History of computing in education (pp. 63-72). Springer US.

McDougall, A., & McCrae, B. (2000). From CEGV 1979 to ACEC 2000: Australian computers in education conferences come of age. Australian Educational Computing, 15(1), 3-6.

Tatnall, A. (2014). Schools, computers and curriculum in Victoria in the 1970s and 1980s. In A. Tatnall & B. Davey (Eds) Reflections on the History of Computers in Education. IFIP AICT V. 424, 246-265.

Walker, R. (1991). The development of educational computing policy in the Victorian school system, 1976-1985. Australian Journal of Education, 353, 219-313.

The Sunrise School and Sunrise Practice

Loader, D. (1993) 'The Audacity of Sunrise', in Grasso, I., & Fallshaw, M. (Eds.). Reflections of a learning community: Views on the Introduction of Laptops at MLC. Melbourne: MLC.

Nevile, L. (1988a) The Sunrise School. A School of the Future Project, ACER (paper presented to the Australian Computer Society, 19 May 1988).

Nevile, L. (1988b) The Sunrise School in the Museum: An interim report of activities in 1988, draft unpublished (held in the print archives of the Melbourne Museum).

Nevile, L. (1990) Sunrise. Unpublished Report: ACER.

Ideas Informing the Sunrise School

Brand, S. (1987) The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin.

Papert, S. (1980) Mindstorms - Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. New York: Basic Books Inc.

Resnick, M. (2017) Lifelong kindergarten: cultivating creativity through projects, passion, peers, and play. Boston: MIT Press

ACER and Sunrise

ACER (1990) Annual Report 1989-90, Australian Council for Educational Research.

The Museum of Victoria and Sunrise

Hancock, J.A., & Thompson, J. (1986) Museum development study: future directions for the development of the Museum of Victoria. Summary report. Melbourne: Museum Development Study Steering Committee.

Rasmussen, C. (2001) A museum for the people: a history of Museum Victoria and its predecessors, 1854-2000. Carlton: Scribe Publications.

Princes Hill Secondary College and Sunrise

Vlahogiannis, N. (1989). Prinny Hill: the state schools of Princes Hill, 1889-1989. Melbourne: The Princes Hill Schools.

Sunrise Centres - MLC, Queensland, Batlow

Braggert, E.J. (1993) Laptop Use at Batlow Technology School. Charles Sturt University.

Finger, G.D. (1995). Evaluating the integration of learning technology in Queensland state schools: A case study of the Queensland Sunrise Centre. Australian Council for Educational Research.

Johnstone, B. (2003) Never Mind the Laptops: Kids, Computers, and the Transformation of Learning, iUniverse, Lincoln.

Rowe, H.A., Brown, I., & Lesman, I. (1992) Learning with personal computers: issues, observations and perspectives. Australian Council for Educational Research.

Ryan, M., Betts, J., Grimmett, G., Hallett, K., & Mitchell, D. (1991) The Queensland Sunrise Centre: a report of the first year. Australian Council for Educational Research.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types