BABEL ISLANDS

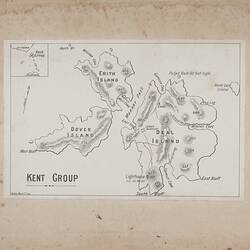

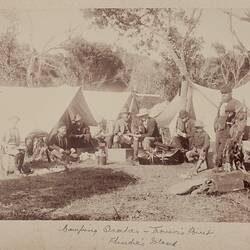

On 18th November, or at the end of our first week, in camp at Trouser's Point, Flinders Island, four of us find ourselves on the nine-ton decked cutter Syren, Mr. William Holt (the owner) in charge, bound for Babel Islands, situated on the other (east) side of Flinders. The rest of the party remains in charge of the camping quarters.

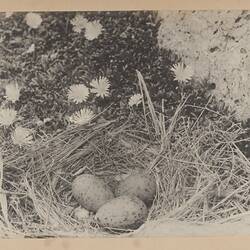

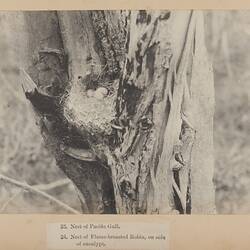

The wind being fair we get an early start, shortly after 6 a.m., and soon are sailing through the beautiful Sound, which is about 15 miles long, between Flinders and Cape Barren Islands. We touch at Isabella Rock, or islet, where, among the granite boulders, are little laps or hollows of tussocky grass, enlivened with patches of white wild flowers of daisy-like appearance. In small holes, about the length of one's forearm, in the ground, under the vegetation we find in scores the little white-faced storm petrel, or one of Mother Carey's chicks.' They are breeding, each sitting in a separate burrow upon one white egg about the size of a pigeon's. Woody Island is next on our track, where we see a flock of about thirty Cape Barren geese. They are extremely shy, and clear down the Sound long before our approach. But a rock between Woody and Little Woody Islands yields us some fine Pacific gulls' eggs, which repose in warmly-lined grass nests, romantically placed amongst flowering vegetation. Then, in more exposed situations, is seen the nesting hollow of the large Caspian tern, with a set of handsome eggs, and protected by a ledge of rock the boldly marked eggs of a black oyster-catcher. The picture is transferred to our camera, the eggs to our collecting basket. Of course, it seems easy work to land on such romantic places, but is must be remembered that every time we have to cast and weigh anchor, and to be rowed to and from the shore in pairs in a small dingy.

We continued to pass down the Sound, with bold and magnificent mountain scenery on either hand. There on the left is Watering Beach, the scene of the late fishing experiment. All the fishermen have returned to their homes except one party, whose camp is discerned near the beach, and who, we hear, are salting fish for market. It is to be regretted the fishing venture so soon collapsed, because experts agree that the Furneaux Group furnishes undoubtedly the best fishing grounds in the Straits, and they attribute this failure to starting at the wrong season, an unlucky prevalence of extraordinary bad weather, and the steamer on trial conveying the fish to market not of sufficient speed.

What extraordinary flocks of birds are these? Through the binoculars we observe they are curlews feeding the low reef near the mouth of the Samphire River. At the sight of our cutter they take wing, when their grey bodies can be counted, not by scores, but by hundreds. It would be interesting to learn when they arrived from their far-away breeding-home in Siberia. We are enticed ashore on this reef. Its higher portions are clothed with saltbush and other low vegetation, which protects nests of Pacific gulls and oyster-catchers. On a patch of short samphire is a colony of the smaller silver gulls' nests, each containing one to three eggs. Some of the more picturesque nests we photograph, while the owners are calling aloud overhead in a very solicitous manner. Human beings no doubt the birds had seen before, but a camera on tripod covered with a dark cloth was a 'scarecrow' too much for them.

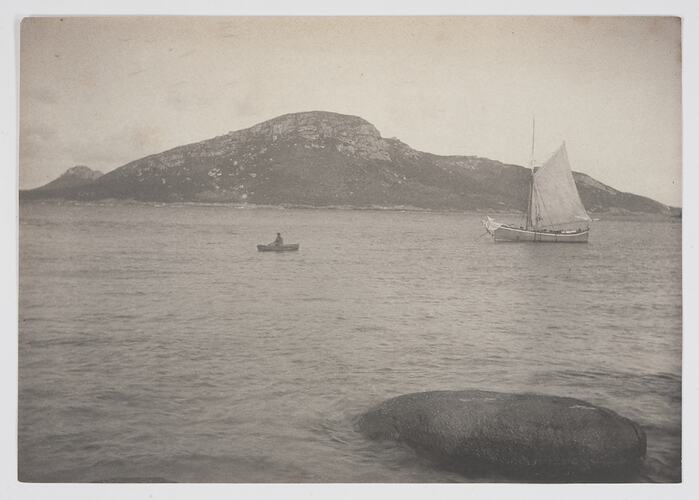

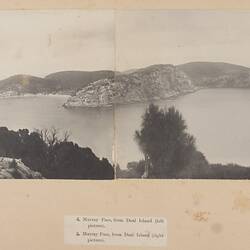

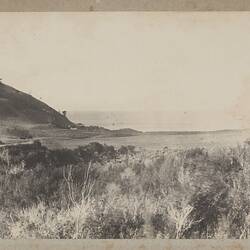

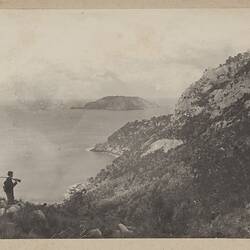

It is well on in the afternoon when we reach the lower end of the Sound and get ashore at Adelaide Bay, on the Flinders side. Some of the party explore inland, which is undulatory and scrubby, and much resembles in general character parts of King Island. I am content to remain near the shore in a serene little corner. Yellow Beach it is called, possibly on account of its sandy shore. It is girt about with trees and rocks almost to high-water mark. Looking south-east up the Sound the view is simply charming. Our cutter, with standing main-sail, breaks the foreground, the low islands the middle distance, while behind, looming in bluish haze, are the forms cloud-capped of Mount Munro, on Cape Barren Island, and the weird peaks of Flinders opposite. Sun-down finds us anchored under some rocky islets in Opossum Harbour, near Mount Eliza, or Vinegar Hill. After supper we (some on deck, others below) are lulled to sleep by the roar of the surf on the outer beach and the fitful squealing of numerous penguins among the rocks close by.

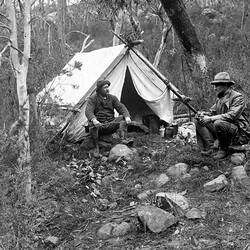

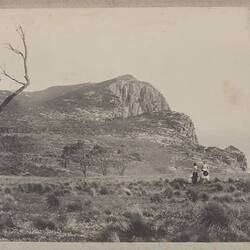

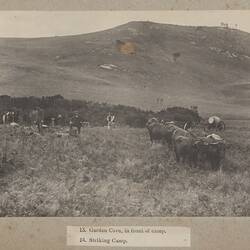

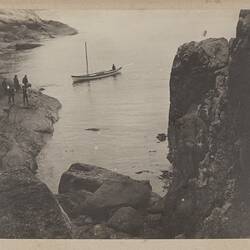

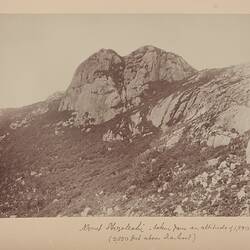

The morn breaks somewhat dull, with a queer atmospheric effect. The barometer has a down-ward tendency. Shall we risk putting to sea to reach Babel Islands, now 15 miles distant, or remain in our safe quarters another day? Time is precious, and we choose the former course, at which the skipper ominously shakes his head. The anchor is weighed at 6 a.m., and we have no difficulty with the tide to run through the rip or 'Pot Boil' at the eastern entrance of the Sound; but once out we commences to roll on the swell of the mighty deep. What with calms and air puffs the sails flap lazily all day, and we scarcely make headway. Worst of all the barometer is still falling, and we see plainly, unmistakably a north-west storm impending. The skipper's face is anxious. Evidently we shall not reach anchorage tonight, although we can plainly see some hunters making a smoke to beckon us to a harbour on Babel Island, only a few miles away. Ah, a land breeze, the precursor of the storm. The sails fill out, carrying us past Babel to an anchorage between the two smaller adjacent islands. No thoughts of supper or sleep to-night, for the wind veers round to the west and blows with all its might into our teeth. Our tiny craft plunges and tugs at the anchor all night, and we shudder, the wind howling through the rigging intensifying our feelings - think if the rope snaps what might happen. In the morning it is clear above, but still blowing fresh from the west. We survey the Babel isles - Babel proper, in front of us, is bold, and about two miles long. The two smaller islets, Cat and Storehouse, are close on either side of us, while the mainland of Flinders is four miles away. At 10 o'clock we risk going ashore in the dingey on the nearest, Cat Island. Some of us wander through tall tussocky grass towards the centre of the island, where an amazing sight confronts us. On a cleared circular space almost 150 yards round are crowded between 2,000 and 3,000 white-plumaged gannets, nearly all sitting each upon a single egg of chalky appearance. The birds are not the least timid and allow us to plant our cameras almost against their feathers. The rest of our party arrive from the beach, having captured some goslings of the Cape Barren goose. However, as the wind is increasing we dare not remain long ashore, but return to the cutter and make for shelter under Babel Island. It takes from noon to 3 o'clock tacking and punching the waves before we are at anchor in a smooth little haven, where two 'darkies' had made an impromptu camp with the sails of their boat, and were accompanied with a pack of seven hungry, long-snorted curs. The islanders were hunting wallaby, interspersed with a little mutton-bird egging. Above us are five or six sharp peaks, ranging up to 650ft. above the sea, the centre one being most conspicuous for its rocky, tower-like appearance, which no doubt suggested the name of Babel to the explorer Flinders, who visited the locality in 1798. The native rockwork near the shore is adorned with pig-face weed (Mesembrianthemum) and other climbing plants which hang over in closely matted trails. Snug as we are at day dawn the wind chops around to the south-east, and blows right in upon us. Our leader and the skipper are on deck, and with some difficulty kedge the craft out, and setting sail bring her to our former anchorage, between Cat and Storehouse Islands. This is now our fourth day from camp. Provisions are becoming scarce. The bread is mouldy, yet we cannot return without renewing our acquaintance with the inhabitants of the wonderful gannet 'rookery'. We first examine a cormorant 'rookery' on Storehouse Island, where these birds have terraced their nests on the ledges and tops of granite boulders, close to the sea on the inner edge of the island.The birds, with their strongly contrasted coats and white under-surfaces, let us approach near enough to obtain photographs, but when they do clear we find ourselves in the midst of 300 to 400 seaweed-built nests, mostly occupied with young in black down, helpless and squeaking like big chickens, or by eggs up to three in number. All the place is whitewashed with the excrement of the birds, filling the air with the most unpleasant of aromas, which is somewhat a sever trial for those naturalists whose stomachs are already sensitive by the tossing of the cutter. Quickly as possible we get over to the gannets on the other Cat Island. The wind is not so high as when we landed yesterday, and in case of an accident we duplicate the photographs of the remarkable feathered congregation. The birds with their white plumage, relieved by black pinions, are at home in all conditions of their domestic economy - the majority sitting closely to their task of incubation, quite oblivious of our presence, loving pairs are fondling each other about the heads, other birds (probably males) are circling round. Now and again one land, oscillating its head in a slow manner, at the same time yawning terribly, slips from its maw a half-digested mackerel or small pike, presenting it to its mate or young. The young are odd-looking creatures in down of snowy whiteness, set off with black face and bill. Although there are young in various stages of growth we observe the majority of the nests, which are regularly placed in rows 30in. apart, con-tain eggs. We take a bucketful. Before we quit the island our sportsman has shot a pair of Cape Barren geese and a few brace of quail for our depleted larder.

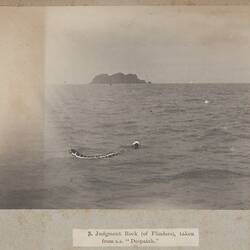

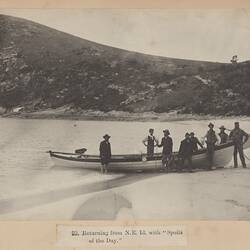

At 9 o'clock the cutter's head is turned towards the sound. We are all day tacking by 'long and short legs,: as the nautical phrase goes, only gaining 10 miles, which finds us awkwardly situated at sundown in the rip just outside the Sound. Here we are exposed to the full swell of the ocean in a place indicated on the chart as 'heavy breakers', caused by a shoal of shifting sand-banks, three or four miles in extent. How our little craft tumbles and reels as great blind-rollers rise, first one and then another, threatening to overwhelm us, and spending themselves with awful roar on a weather shore close by. Out situation seems desperate. The sun has sunk to rest, leaving us in the middle of an unrest in the boiling rollers of the Rip. That would not signify had we any weigh on. Moreover, the tide will soon be against us. Occasionally an air-puff shakes our own sails, and aided by our toiling in turns at a long oar we just manage to scrape through the 'pot boil' and anchor in mid channel at 8 o'clock. Here fish - flatheads and pike - caught on the road down are quickly frizzling in the pan, and never was supper more thankfully eaten than that partaken by us on the safe side of the terrible 'pot-boil.' A favourable breeze springs up at the first streaks of dawn, which we taken advantage of, and flying up the Sound with a free sheet arrive in camp in time for breakfast. Thus ends five days of adventure on the trip to Babel Islands.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types