Note: This article includes racist slurs as it is quoting a historical text. Such words and sentiments are not condoned by Museums Victoria which considers them to be racist. Historical distance and context do not excuse or erase this fact.

CAPE BARREN ISLAND

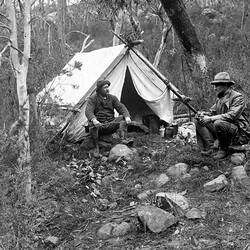

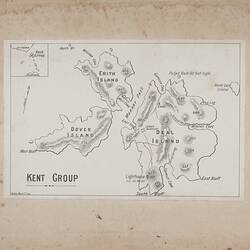

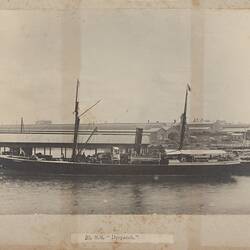

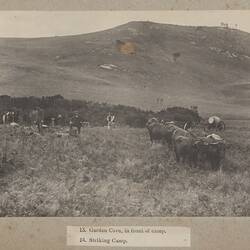

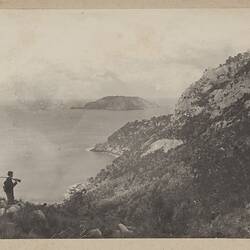

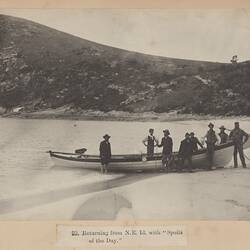

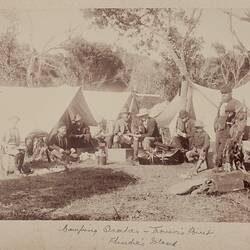

On the 24th November a strong nor'-wester blows right into our camp harbour. It moderates about noon; when we are all again on board the Syren in charge of 'Skipper' Holt and his 'only mate,' his young son. We are this time bound for Cape Barren Island, nine or ten miles across the Sound. Arriving at the half-caste settlement, or rather the Furneaux Mission Station, we are hospitably entertained by Mr. Ed. Stephens (the schoolmaster) and his family. The day following is spent upon the island, where we find much of interest. The half-caste settlement numbers about 125 souls, but about 40 of the men, women, and children are absent mutton-bird egging on Chappell Island, at the entrance of the Sound. The dwellings of the islanders are not very pre-tendinous, nevertheless are clean and tidy. Naturally the people themselves are retired and modest, well spoken, exemplary in conduct - in fact, quite gentle folk in their homely way. Much of this training is through the excellent oversight of the Tasmanian Government. People who through no fault of their own might have become outcasts now live in a respectable and Christian-like manner. There are 47 children on the school roll. Mr. Stephens is not only their instructor in temporal, but also in spiritual training, in which, with his good wife, he takes especial delight. We could not help looking upon the islanders, more especially the children, with unmixed interest, knowing that their great-grand-ancestors were white on the father's side and aboriginal on the mother's. In the olden days men who were tired of the restraint of civilisation and with an intense desire for romantic adventures, others to escape the clutches of the law, and some, dis-carding their real name (in some instances of good British families, and in the physique of their descendants after several generations and strange admixture of colour we see proof of the old adage that 'blood will tell'), and adopting another sought these islands. Hunting, fishing and sealing were the chief occupations of these men, and when they dwelt on the thought, 'It is not good that man should be alone,' adventurous souls in fragile boats crossed over to Australia (or New Holland in those days), and by honourable proposals, kidnapping, or by bloodshed obtained female companions from the dusky native tribes, while some were taken from Tasmania. The descendants of these from Port Phillip are clearly traced by the straight hair; those with curly heads and rounded faces point to Tasmania as being the home of their maternal ancestors. Had it not been for the great affection of the native women for their white-faced husbands and love of the men for the women, the whole race of half-casts would probably have had no existence or been dispersed. There were many places on the islands to which the women with their children escaped, and they were fed secretly by the men, when the order came that the last of the exiles placed on Flinders Island at the instance of George Augustus Robinson, of philanthropic fame, and all other natives were to be transported to Hobart and Oyster Cove. The women (but none of the exiles) in concealment resumed their freedom and lived to be the progenitors of the interesting race we see to-day, rejoicing in the names of Maynard, Beedon, Smith (assumed name), Everett, Mansell, and others.

During tea an entertainment is suggested, and although only two hours' notice is given by crier all the available inhabitants meet in the schoolroom at 8 o'clock, Mr. Stephens presiding. Messrs. Bradly and Ashworth with suitable recitations, and Mr. Gabriel on his melodious flute, fairly enthral the dusky audience, and the plaudits that greet the performers at the termination of the programme are a genuine and hearty compliment.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types