CHAPPELL ISLAND

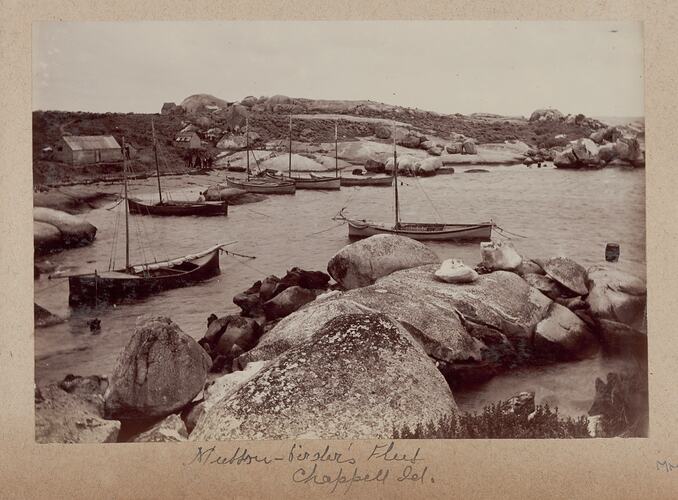

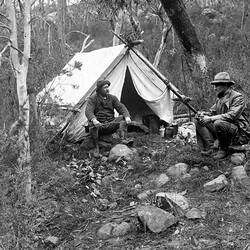

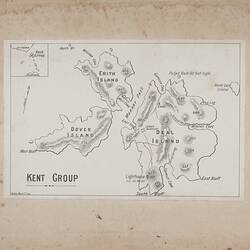

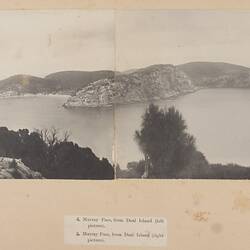

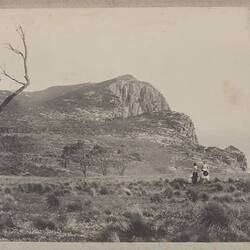

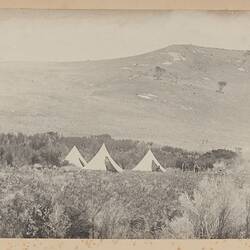

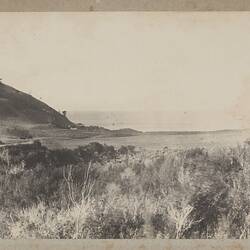

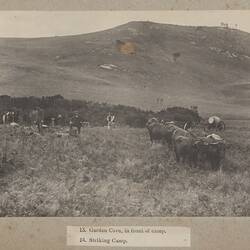

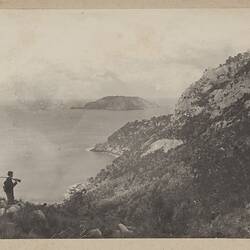

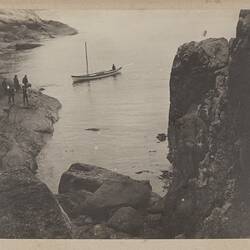

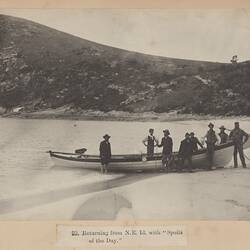

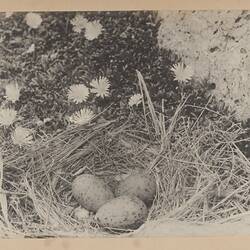

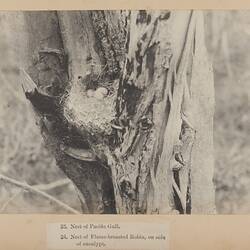

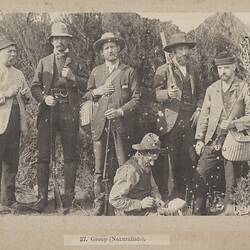

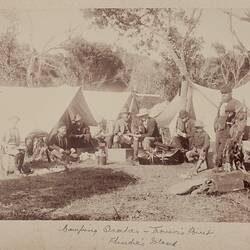

On the 26th November, leaving Sandford Bay or the Settlement, a decreasing wind affords an opportunity of beating across to Chappell Island, or Humpy as the islanders call it, to witness the mutton-bird egging operations. As before mentioned Chappell Island is at the entrance of Franklin Sound, about five miles out. The island is about two miles long by a breadth of a mile, is remarkable for the cone-shaped hill in the centre, rising to a height of 650ft. Chappell is par excellence: the mutton-bird rookery of the Straits, its whole surface under the tussock grass, salt bushes, large crops of nettles, gardens of yellow immortelles, &c., being completely honey-combed with the burrow-like nests of the sooty-plumaged birds. Thither the islanders repair twice a year - about a week towards the end of November for eggs, and again in the autumn to secure and preserve the young birds, which appear to be the staple food of the inhabitants, both white and dark. When we arrive egging is at its height. Our cutter is moored to granite boulders in a serene little cove on the east side, while we walk over to Shagboat Harbour on the south side, which accommodates the bird-eggers' fleet of seven double-ended boats. The men, women, and children (about forty) are ashore, some camped in sheds thatched with tussock-grass, some under the lee side of huge rocks with their boat sails converted into tents. We obtain novel and characteristic photographs of the boat harbour and fleet, groups of bird-eggers, and bird-eggers at work.

At low tide some of the expert swimmers oblige us by diving into subterranean caverns for the sea fan (Gorgonia), of great beauty, in pink and yellow branchlets of coral-like appearance. The rare Ceratella fusca of marine zoologists is also secured, which somewhat resembles the sea fan, only is smaller, and of a brownish colour. The Ceratella was first discovered during our Kent Group expedition, and afterwards described by Professor Spencer.

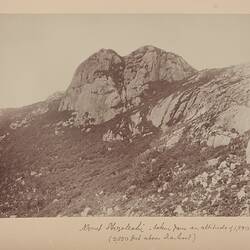

We remain the night upon the island, to renew our acquaintance with the incoming birds - a scene familiar to most Australian ornithologists. In fact, no person should call himself an ornithologist unless he has been the witness of the most wonderful bird flights in the Southern Hemisphere. About sundown the forms of birds are just discerned dodging over the horizon. Quickly they approach in perfect crowds, not direct but circling swiftly in all directions round the island. We are looking across the channel, where the bold peaks of Flinders, pierced by a billowy thunder-cloud and lighted up by the western twilight, afford an excellent background to the multitudes of dark birds as they cut past us to and fro. With darkness coming on, apace the birds venture over the island, and by 8 o'clock nearly all are landed. Then is a row and hubbub of thousands upon thousands of birds in their burrows, croaking, calling, fighting each other, or battling with snakes - such a pandemonium one is never likely to forget. After a surfeit of these marvellous scenes and sounds we retire to rest - some on land on a comfortable tussock-made couch, protected by the boat's sail, others afloat in the boat itself.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types