Melbourne's Industrial & Technological Museum first opened its doors to the public on Friday, 9th September 1870, following an inaugural public lecture entitled 'On the Methods of Diffusing Technical Knowledge' presented by Professor Frederick McCoy to an audience of almost 200, in the museum auditorium the previous evening.

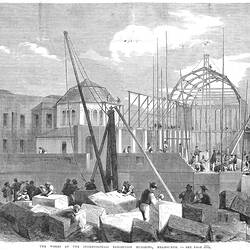

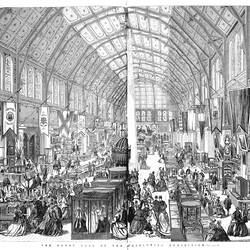

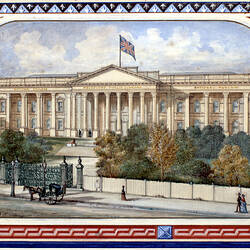

The I&T Museum's first home was in the Great Hall and adjoining Rotunda, designed by Melbourne architects Reed & Barnes for the Intercolonial Exhibition of 1866-67, and constructed behind the Public Library on Swanston Street, where the Dome Reading Room of the State Library now stands. The museum had its origins in the international movement to promote the application of arts and science in the advancement of industry, which had begun with the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, London, and in turn spawned the establishment of the Science Museum at South Kensington in 1857, on which the Melbourne museum would be modelled.

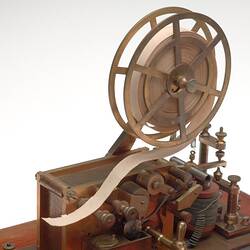

Public education was the raison d'être of the I&T Museum over its first two decades, with weekly evening public lectures offered on a variety of technical topics attracting average audiences of 200. From early 1871, courses were offered to students of any age or background for a modest fee with twice weekly lessons and practical laboratory sessions. Initial subject offerings included classes in chemistry, mineralogy, mathematics, practical geometry, mechanics, industrial design, painting, mechanical drawing, modelling and model-making. By far the most popular, however, was the telegraphy course introduced in March 1872, with places entirely booked out by young women hoping to gain employment with the Post & Telegraph Department. Students for the other subjects included druggists, miners, wine merchants, mining engineers, draftsmen, clerks, teachers, civil servants and some prominent local manufacturers such as John Buncle of the Parkside Ironworks. In 1876, the first pharmacy apprenticeship training in Victoria was introduced by the Museum. The early teaching programs of the I&T Museum developed in a period during which there were few other opportunities for technical education in Victoria. The Ballarat School of Mines, became Victoria's first technical education college when it was established a month after the I&M Museum opened, but it initially developed slowly with only four students enrolled by the time classes started at the beginning of 1871. The University of Melbourne had introduced a Certificate of Engineering in 1861, becoming the first tertiary institution in Australia to do so, but a decade later only eight students in total had completed the full three years of coursework required to graduate. Technical schools at a secondary level and most other tertiary technical colleges in Victoria were not established until the early 20th century.

James Cosmo Newbery was appointed as the first 'scientific superintendent' (or curator) of the I&T Museum, at salary of £350 per annum, with George Ulrich as his assistant in charge of the mineral collections. Born in Italy, in 1843, Newbery had trained at Lawrence Scientific School, Harvard and the Royal School of Mines, London. In June 1865, he was appointed as mineral analyst & assayer, to Geological Survey of Victoria, but his position was abolished in 1869, after which he worked as a consultant to mining companies in similar capacity. On his appointment to the I&T Museum, he managed to negotiate approval to continue his private practise on a part time basis supplementing his income and enabling him to maintain connections with Victoria's then vibrant mining industry. Ulrich had previously been lecturing at the University of Melbourne, and would later resign in 1878 to take up the professorial chair in Mining & Metallurgy at Otago University, in New Zealand. He was replaced by Oliver R. Rule and then in 1892, by Richard H. Walcott, who had been a student of Ulrich's at Otago.

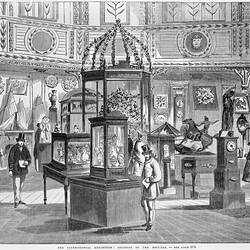

The nucleus of the I&T Museum's early collections consisted of exhibits that had been displayed at the Intercolonial Exhibition of 1866-1867, together with a collection of mining models, miners' tools and agricultural equipment models that McCoy had put together from 1856 as part of the National Museum based at the University. The one exception were the prized Nordstrom mining models, which McCoy refused to transfer to the new museum and managed to retain until his death in 1899.

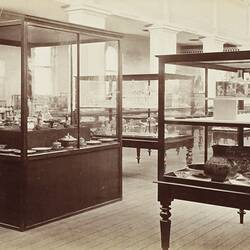

The collections were initially put on display in the former Intercolonial Exhibition Hall behind the Public Library, while the adjoining Rotunda was fitted out as a lecture hall and temporary laboratories were established in the old Police sheds at the rear of the building. Aside from their active teaching program, Newbery and Ulrich set about amassing a sizable collection numbering over 10,000 'specimens' within two years. Newbery organised the material following the same principals as the Museum of Irish Industry in Dublin (founded in 1854) and the Industrial Museum in Edinburgh (established in 1866). Displays were grouped into four main categories:

1. Geology & mineralogical specimens

2. Zoological - animal products & the their industrial uses

3. Phytological - processed vegetable products

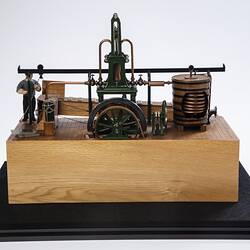

4. Machinery & models of inventions

Newbery purchased minerals, industrial products and gave prominence to displays of pottery and glassware produced by local manufacturers. He also commenced a firearms collection to provide training opportunities for mechanics and gunsmiths.

The opening of Working Men's College (later the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and today RMIT University) in 1887, saw many of the earlier teaching functions of the I&T Museum gradually transferred over the next few years to the neighbouring facility, on the opposite side of Latrobe Street.

In 1893, the I&T Museum moved into a new larger purpose-built exhibition hall with adjoining galleries, constructed near the eastern end of the Swanston Street site, close to Russell Street, although visitors still entered the museum through the Public Library and Art Gallery, which also shared the site. The renaissance was short-lived, however, because Victoria was shortly afterwards plunged into a prolonged economic recession, with funding for the museum drastically reduced, causing all further development of the collections to practically cease. In 1895, Newbery died after protracted illness and was replaced by R.H. Walcott, but due to the ongoing fiscal constraints he was appointed only as acting curator.

After Frederick McCoy also died in 1899, his successor Baldwin Spencer instigated the relocation of the National Museum of Victoria from the University of Melbourne to the Swanston Street site, having convinced the Trustees of the institutions that the natural history collections should be housed in the 1893 building, which would be renamed McCoy Hall. Although it was proposed that alternate space would be offered to the I&T Museum, it was not forthcoming due to ongoing budgetary constraints on the government, and the I&T collections were largely packed up and placed in storage in the basement vaults. At the same time, the reference mineral collections of the I&T Museum were transferred to the National Museum, where Baldwin argued they were better suited, and Walcott moved with them to continue the task of their cataloguing and care.

Renewal of the Industrial & Technological Museum

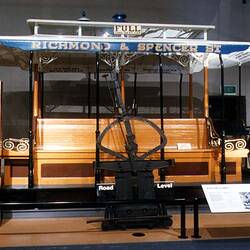

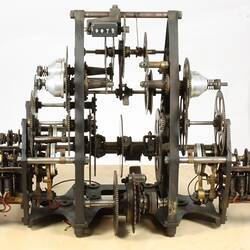

After almost 15 years in hibernation, the Industrial & Technological Museum re-opened to the public on Monday 17th May 1915, without fanfare, perhaps because of the context of WWI and the public anxiety over the Gallipoli Campaign that had commenced less than a month previously. Two figures were instrumental in the lead-up to the re-opening. The first was George Swinburne, a British born mechanical engineer with largely practical training and limited formal education, who had arrived in Victoria in 1886 and became a leading figure in the Australian gas industry. In 1907 he had provided a £3,000 endowment that lead to the establishment of the Swinburne Technical College in Hawthorn (now Swinburne University), and three years later he joined the Trustees of the Public Library, Museums and National Gallery. He began actively urging other Board members of the need to reopen the I&T Museum to support the growing interest in technical education. The second champion of the I&T Museum cause was John Monash, a young professional engineer who'd become a pioneer in reinforced concrete construction and in 1910, as President of the Victorian Institute of Engineers, began to canvass support from bodies such as the Mining Engineers, Chamber of Mines, the Royal Society of Victoria, Australian Natives Association and the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects. With the completion of the new Dome Reading Room for the Library in 1913, the previous reading room in the Queens Hall became surplass to requirements and arrangements were made to repurpose the space as an exhibition gallery for the I&M Museum collections. Walcott returned to his former role in 1914 to prepare for the opening and significant acquisitions were made over the next few years to modernise the displays, with a greater emphasis placed on working models and exhibits that explained how technology worked.

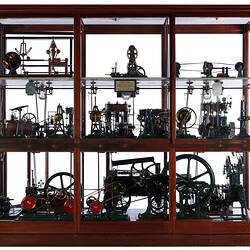

R. H. Walcott retired as curator in 1935, after 43 years' service to the two museums. He had been a quiet and unassuming advocate for the museum's technological collections but struggled through several periods of financial adversity when it was difficult to get any government funding for acquisitions or extensions to the display space. Without a dedicated building of its own, the I&T Museum was forced to sit cheek by jowl with the Public Library, Art Gallery and National Museum on the cramped Swanston Street site. Following WWI, a significant collection of surplus military aircraft engines were acquired at modest expense and Walcott worked with local industries to establish displays depicting processes involved in the manufacturing of products ranging from felt hats, to fertilisers, radio valves and electric light globes. Responding to the increasing complexity of technology, leading overseas museums were developing new display approaches that better demonstrated the internal workings of complex machines and Walcott followed these trends securing the I&T Museum's first sectioned motor cycle and automotive engines and electric motors. Meanwhile, the skills of Professor Wilfred Kernot of the University Engineering Faculty were called upon to set up the first elements of a large Working Models Case, that would become one of the most popular exhibits over subsequent decades.

One of Walcott's key successes was to secure the Duigan biplane - the first powered aircraft designed and flown by an Australian - although space was so limited he had to arrange for it to be hung from the ceiling of Queens Hall. Ironically, several significant historical horsedrawn vehicles and motor vehicles offered to the Trustees during the interwar years could not be accommodated in the I&T Museum's meagre space and were initially given to the Public Library to display.

In 1944, the I&T and natural history museums formally gained independence from their progenitor, the Public Library, with a separate Board of Trustees being established to manage the two 'National Museums'. At the same time the Industrial & Technological Museum's name was changed to the Museum of Applied Science of Victoria, reflecting a transition in the institution's main fields of activity, with the earlier emphasis on artisan instruction passing to other specialised teaching colleges. Displays were modernised and the museum gained some much-needed additional space, expanding from Queens Hall into the adjoining Barry Gallery, where new comprehensive displays of clocks & watches and firearms & weapons were installed. A program of topical and changing displays was introduced featuring the application of science in new fields of human endeavour from the manufacture of plastics, antibiotics and automotive engineering to atomic energy. In 1946, the museum also gained custodianship of the former Melbourne Observatory that had been closed by the government at the end of WWII, allowing evening public astronomy sessions to be introduced with the assistance of honorary guides from the Astronomical Society of Victoria.Institute of Applied Science

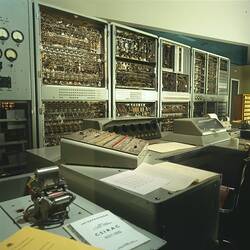

In 1961 a further transformation took place when the name was changed again to the Institute of Applied Science of Victoria, reflecting at least a desire to be seen as more of a collaborator with industry, rather than merely its chronicler. Under a new dynamic director, the organisation embraced its new focus as an ambassador of industry and educator through exhibitions, offering expanded formal education programs for both primary and secondary school students. By 1970, seven teachers were seconded to the museum from the Education Department to support these programs and a series of public lunchtime lectures for adults had been introduced. A radiocarbon dating laboratory was established, managed by Anne Bermingham, the organisation's first female professional scientist, and in December 1965 a planetarium was added providing a popular new attraction to a generation obsessed with the excitement of space travel and the ambition of placing 'Man on the Moon' before the decade was out.

Science Museum of Victoria

The transfer of the National Gallery of Victoria to its new home on St Kilda Road, in 1969, provided scope for the Institute of Applied Science to further expand its exhibition space, although the Queens Hall was handed back to the library. In 1971, further transformation occurred when the Board of Trustees was replaced by a managing Council, and the organisation was renamed as the Science Museum of Victoria, coming full circle to reflect the title of the London based institution that had been a major inspiration for its formation a century earlier.

Finally, in July 1983, the Science Museum merged with its senior affiliate, the National Museum of Victoria, to form the Museum of Victoria, creating Australia's largest and most diverse scientific and cultural organisation. Today the inheritance of these predecessors forms part of the museum's Society and Technology collections and curatorial programs.

References:

1. Rasmussen, C., A Museum for the People - A history of Museum Victoria and its predecessors, 1854-2000, Scribe Publications in association with Museum Victoria, Carlton, Victoria, 2001.

2. Treasures of the Museum, Victoria, Australia, Museum Victoria, 2004.

3. Perry, W., The Science Museum of Victoria: A History of its First Hundred Years, Science Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, 1972.

4. National Museums of Victoia Year Book, 1948, Trustees, Melbourne, Victoria, 1948.

5. Report of the Trustees of the Public Library, Museums and National Gallery of Victoria for 1870 to 1944 (Annual), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Melbourne, Victoria, 1870-1945.

6. Museum of Applied Science of Victoria Annual Report, 1945 to 1951, The Trustees of the National Museums of Victoria, Melbourne, 1945-1951.

7. Museum of Applied Science of Victoria, Report of Activities, for the Year Ended 30th June 1952 to 1960 (Annual), The Trustees of the Museum of Applied Science of Victoria , Melbourne, 1952-1960.

8. Institute of Applied Science of Victoria, Report of Activities, for the Year Ended 30th June 1951 to 1969 (Annual), The Trustees of the Institute of Applied Science of Victoria , Melbourne, 1961-1969.

8. Science Museum of Victoria, Report of Activities, 1970 to 1983 (Annual), Council of the Science Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, 1970-1983.

9. Museum of Victoria Annual Report, 1983-84 to 1990-99, Council of the Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, 1984-2000.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types