The sixties and seventies are still vivid in the collective psyche, having a mythology of their own that survives through the multitude of cultural interpretations present in the media. In his book on protest movements in Australia, Graham Hastings notes how 'in reality it was a lot more than just about getting stoned, listening to Jimmy Hendrix and wearing peace medallions' (Hastings, 2003). Political activism was one of the main aspects that helped shape this generation and the war in Vietnam in particular was a cause that had millions of people rallying around it.

1968 - 'year of the revolution'

This year marked important street protests led by students taking place in France, Czechoslovakia, Mexico and Japan, among others. Academics trace this increase in political sentiment among young people back to the post-war economic boom as well as a significant increase in university education. It is no coincidence then that the anti-war movement was born on campuses, in fact 'the defining character of the protest movements of the 1960s and 1970s was the student protester' (Wood, 2013). In 1968 civil unrest also started escalating on American campuses on a bigger scale. Interestingly, that same year the Australian magazine The Bulletin published an article referring to the protest movements asking 'Can it happen here?' Mere days later students at Monash University provided a clear answer by carrying out the first mass occupation of a building on campus.

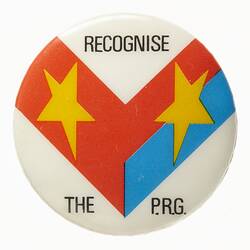

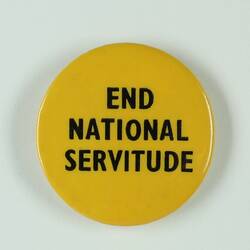

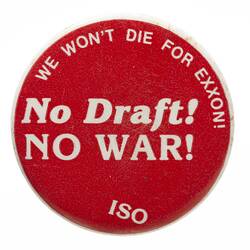

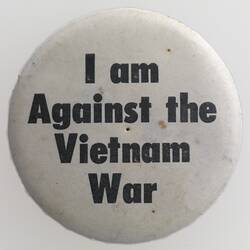

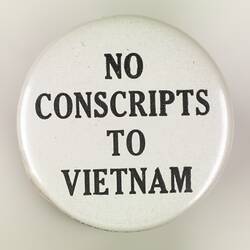

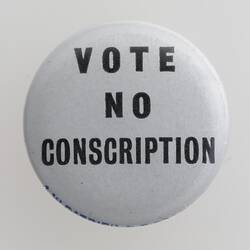

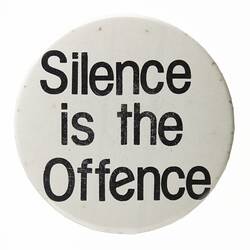

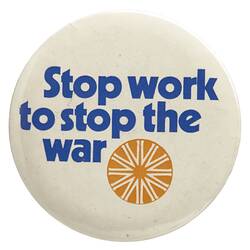

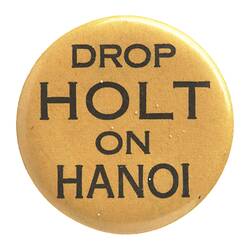

Badges as symbols

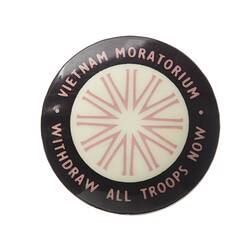

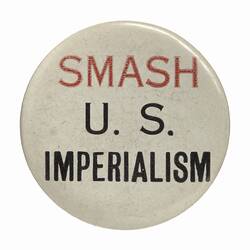

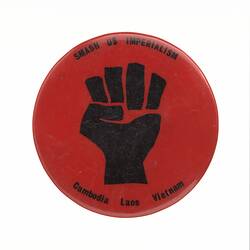

Museums Victoria Badge Collection encompasses the landmark issues of the Vietnam War period: draft resistance, opposition to imperialism, sit-ins, communism, aid appeals and peace. It is not only a set of representative objects to consider today in order to understand the sixties, it also represented a crucial cross-section of material culture at the time. Badges were one of the key ways for protestors to construct their identity and disseminate their views. Many peace activists would amass hundreds of such badges into their personal collections, like many Museums Victoria donors actually did. Wearing public signs to convey anti-war sentiment was a powerful act at a time when the 'cultural conflict [.] played out as a clash of symbols: long hair, the flag, the draft card,' to which one could presumably also add the sunburst Vietnam Moratorium symbol, the raised fist and many more.

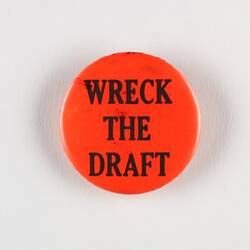

Draft Resistance

These new social movements led by young educated radicals had a character of their own. Traditional politics were replaced by a collective democracy and street demonstrations. Although most of the actions were supposed to be non-violent but this stance was often undermined. Conscription in Australia started quite early in 1964 and sparked a strong backlash. The Melbourne Draft Resistance movement was quite robust, as is evident from the very language employed. They were not simply interested in opposing the draft, instead proposing to 'wreck' it. A badge in the Museums Victoria collection also bears the slogan 'Wreck the draft', showing the passionate nature of student activism. The Draft Resistance Movement at Monash and Melbourne Universities also put together sanctuaries for people fleeing from the police. Organisations like the Students for a Democratic Society ran campaigns such as Fill in a Falsie, encouraging people to complete as many false conscription forms as possible.

Moratorium Marches

One of the staples of the anti-war movement was the Vietnam Moratorium Rally. In 1968 the Vietnam War escalated abruptly with events such as the My Lai massacre, the mass killing of hundreds of unarmed civilians and the Tet Offensive, a large military campaign where many soldiers died in battle. The first New York large-scale protest happened in 1969 and was to a large extent an answer to the developments in Vietnam. Its success incited the first Melbourne march that took place in 1970 and had 100,000 people in attendance. It is hard to gauge the exact impact of these rallies on the decision of the government to put a stop to the war effort, but it certainly helped shape social attitudes more generally. The Museums Victoria badge collection holds dozens of Vietnam Moratorium buttons, most of which feature the sunburst logo. Disseminating badges with the same logo at all three Melbourne Moratoriums between 1970 and 1971 was a very efficient way to create the feeling of a collective goal. This shared experience was especially important at a moment when the anti-war protests moved beyond a fringe campus activist scenario into the mainstream.

Sectarian Divisions

One of the main misconceptions about the anti-war movement of the time seems to be the idea that it was a coherent one. The Political and Protest Badge Collection numbers over 70 pins that deal in some way with the Vietnam War. One sees the same visual motifs and slogans being repeated across the collection. Moreover, sharing messages across campaigns in different countries was an important characteristic of the peace movement. This meant that the same slogans and symbols would be present on materials in the UK and America as well as Australia. However, by 1971, the anti-war movement in Australia had broken down into many factions disputing the direction of the campaign. Brian Medlin remarked how 'the war is too important to become a battleground for differing philosophies within the peace movement' (Hastings, 2003) but that is exactly what occurred. For example, at the end of the seventies, there was definitely a feeling that the Communist Party of Australia wanted to overtake the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign and run it on their own terms. However, it ended up being an organisation open to input from anyone. This became a central point of contention inside the left-leaning movement. Similarly, the rank and file of protesters consisted of socialist students supporting the Viet Cong but also anarchists that rejected both the North and South Vietnamese government. Certain members of the Monash Labour Club decided to go a step further and actually fundraised for the Viet Cong, which proved to be very controversial at the time. Women also often felt left out of the campaigns and would start their own separate groups. The traditional peace groups like the Youth Campaign Against Conscription were left behind entirely for not being revolutionary enough. There were also divisions in terms of usage of slogans. The Vietnam Action Committee chose 'Troops out now' as a concept to rally around. However, some ultra-leftist factions felt that it was not targeted enough and focused on the slogan 'Smash US imperialism.' The majority of these groups feature in the badge collection, as well as both of the slogans. It is therefore worth mentioning how the variety of the badge collection actually reflects the heterogeneous nature of the anti-war campaign rather than its unity.

Reference List

Hastings, G. (2003) It can't happen here: A political history of Australian student activism. Adelaide: The Students' Association of Flinders University

Lorimer, D. (2003) The movement against the Vietnam War - its lessons for today. Available at: https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/movement-against-vietnam-war-its-lessons-today-0 [Accessed 02 Dec. 2016]

McIntyre, I. (2009) How to make trouble and influence people: pranks, hoaxes, graffiti & political mischief-making from across Australia. Carlton, Vic: Breakdown Press

Vassiley, A. (2010) Smash the Draft!' and other tales: a snapshot of student activism at The University of Western Australia, 1969-1971. The New Critic, [online] Issue 13. Available at: http://www.ias.uwa.edu.au/new-critic/thirteen/vassiley [Accessed 02 Dec.2016]

Wood, K. (2013) Student Activism. Available at: http://archives.unimelb.edu.au/explore/exhibitions/past-events/protest!-archives-from-the-university-of-melbourne/student_activism [Accessed 02 Dec.2016]

More Information

-

Keywords

Political Protests, Vietnam War, 1959-1975, Vietnam Moratorium, Anti-Conscription Campaigns, Protests, Activism, Anti-War Demonstrations, Peace, Peace Movement, Draft Resistance, Wars & Conflicts

-

Authors

-

Article types