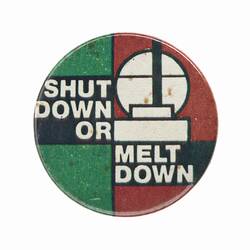

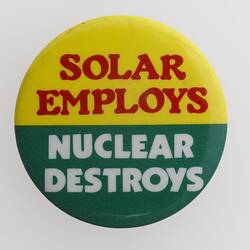

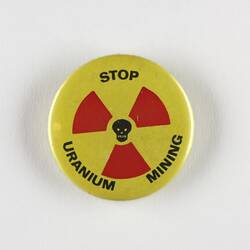

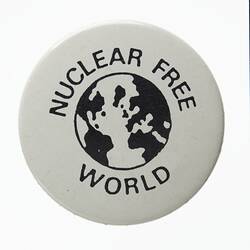

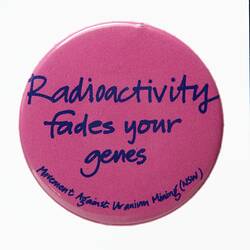

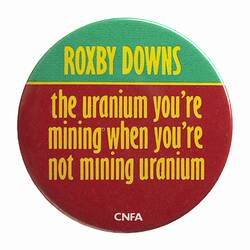

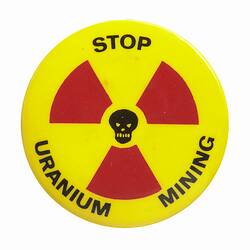

The prominent political tensions of the Cold War and the Arms Race bred a global climate of fear in the 1980s and it meant that nuclear disarmament became the main focus of activism in this decade. In the 1970s Australian anti-nuclear protests were scarce, with the movement evolving into full-blown mass protests in the 1980s. Protests at the time tackled an immense range of issues, from links between capitalism and nuclear power, concerns over how uranium might fuel the global weapons cycle, harm to the environment, the ethical and health-related impact on Aboriginal communities and security risks, among others. However, one of the main strains of activism in Australia was the campaign against uranium mining, as Australia holds the world's largest reserves of this material. In 1986 the government signed a Nuclear Free treaty which pledged that the country will hold no nuclear weapons, power stations or vessels. Nonetheless, uranium mining and export carried on and the presence of American bases, nuclear warships and French nuclear tests in the Pacific also continued unhindered.

The legacy of the anti-war movement

Mass protest movements and civic unrest, in the contemporary understanding of the terms, can loosely be traced back to the American civil rights movement of the 1960s. Evolving from that, the opposition to the Vietnam War in the late sixties and early seventies was the event that shaped an entire generation and truly popularised protest. In Australia the anti-war movement was also incredibly prominent, especially in the form of student activism. The anti-nuclear protests of the 1980s can be seen as an organic continuation of the earlier movements of dissent. Timothy Doyle has noted how protests taking place between 1960 and the mid-1980s had a shared character: unrestrained outsider politics, focusing on mass mobilisation, lobbying and putting pressure on the government. After the mid-1980s protests moved towards a more corporatist, insider approach whereby activists would seek to collaborate with the government in order to change policy. (Doyle, 2001)

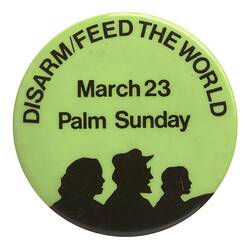

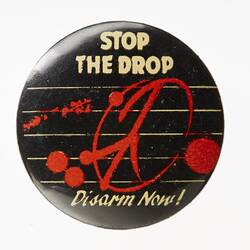

As part of this early oppositional character, both the anti-war and anti-nuclear campaigns relied on marches as a main form of expression. Palm Sunday Rallies, for example, were anti-nuclear demonstrations taking place on the last Sunday before Easter. In 1982, the Melbourne event had around 100,000 attendees, the same number as the most popular Vietnam Moratorium of 1971. Palm Sunday had reached 300,000 participants by 1985, becoming one of the biggest social movements in Australian history. There is a Palm Sunday badge in the collection bearing the message 'Disarm/Feed the people.' This emphasises the connection between the anti-nuclear and wider peace movements.

Folk Devils

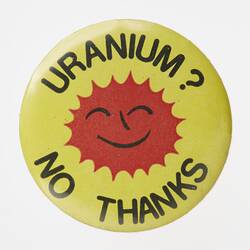

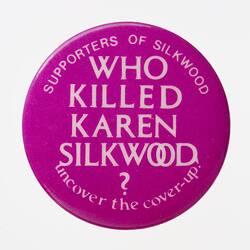

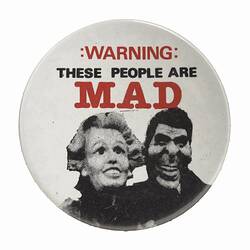

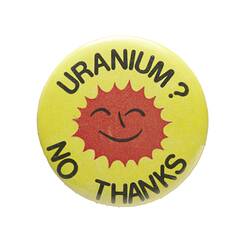

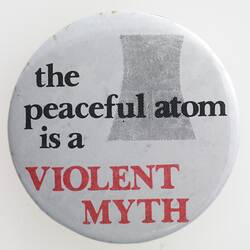

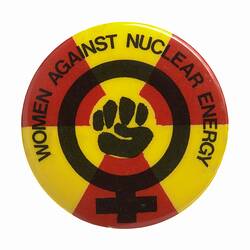

The media at the time focused on the most extreme cases of activism and sought to convey the protestors' lack of respectability. Regardless of their demands or actions, activists were seen as 'folk devils' and branded as subversive. For instance, the smiling sun logo accompanied by the words 'Nuclear Power? No thanks' was specifically designed by a Danish activist to foreground polite dialogue. Museums Victoria holds dozens of badges with this symbol, as it was one of the most popular designs and it became the unofficial international logo of the anti-nuclear movement. In contrast, an event like the Women's Peace Camp of 1983 took a different approach, as that year 100 women broke into the Pine Gap base and upon their arrest they all claimed their name was Karen Silkwood. She was a chemical technician and labor unionist that had entered the spotlight when she died in mysterious circumstances after publicly criticising the nuclear industry. The collection holds a badge reading 'Who Killed Karen Silkwood?' This is one of many examples of the confrontational stance that the protestors took in trying to pressure the nuclear industry.

The 'myth of the common goal'

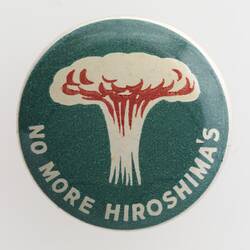

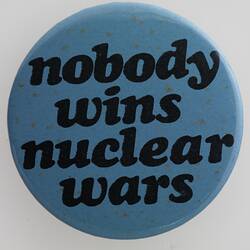

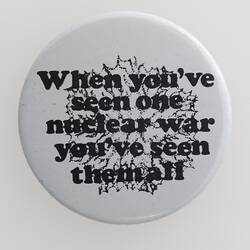

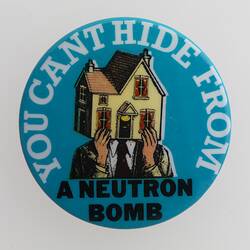

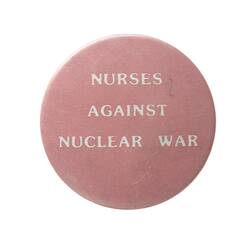

In his book Green Power, Timothy Doyle uses this phrase to refer to the lack of a single coherent ideology inside of the environmental movement. This can be extended as a description of the anti-nuclear movement as well. Its diverse values and goals meant that it should be regarded more like a network of more or less interrelated movements, rather than a cohesive bloc. (Doyle, 2001) First of all the variety is reflected in the campaigns, like anti-uranium, anti-base, land rights, environmental. Secondly, it also comes through in approaches within a single campaign: for example organisations campaigning for the closure of all American bases in Australia versus mere non-expansion of existing bases. Like in the case of the Vietnam War, the Anti-Nuclear Badges reflect the variety of approaches through the sheer number of different slogans the collection boasts.

Reference List

Branagan , M. (2014) The Australian Movement Against Uranium Mining: Its Rationale and Evolution. International Journal of Rural Law and Policy Mining in a sustainable world, special edition 1. Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlRuralLawP/2014/4.pdf [Accessed 02 Dec.2016]

Doyle, T. (2001) Green Power: The environment movement in Australia. 2nd edition. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press

Green, J. (1998) Australia's anti-nuclear movement: a short history. Available at: https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/australias-anti-nuclear-movement-short-history [Accessed 02 Dec.2016]

Jonathan S. (2015) The Australian Nuclear Disarmament Movement in the 1980s in Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Labour History Conference, eds, Phillip Deery and Julie Kimber. Melbourne: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 2015, p.39-50.

More Information

-

Keywords

Nuclear Disarmament, Political Protests, Protests, Uranium Mining, Environmental Activism, Activism, Uranium Mines, Anti-Nuclear Protests, Nuclear Power

-

Authors

-

Article types