Badges have a longer history than it might seem at first. It is recorded that European holy shrines produced millions of pewter badges for pilgrims as early as the 12th century. In a situation not entirely dissimilar to the contemporary gift shop, people would purchase the buttons at shops surrounding the shrines. At this time, there was a belief in the talismanic properties of such objects, but it was also a means of conveying one's status as a devout Christian (Atwood, 2004). This aspect of badges as creators of identity has been retained in the way they are employed in modern times. Philip Atwood notes how the political badge conveys 'a belief that "ordinary people" can help make a difference' (Atwood, 2004). In 1991, an unnamed sticker creator similarly remarked that 'it's the "people's art" - the means of self-expression for losers outside the culture production monopoly' (McIntyre, 2009). Accessible, cheap and easily made, buttons have come to define mass movements. Although many pins held by Museums Victoria were made by established businesses such as Patrick Brothers in Melbourne, a significant number were made using a semi-automatic machine called Badge-a-minit. This highlights the DIY aspect of the protest movement, specifically in the 1970s.

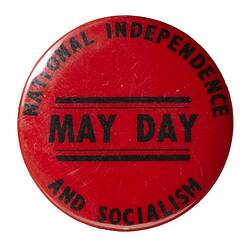

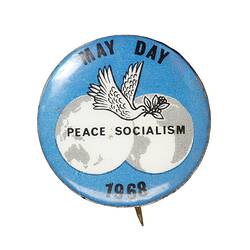

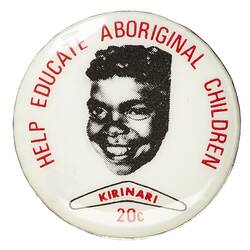

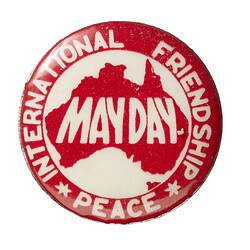

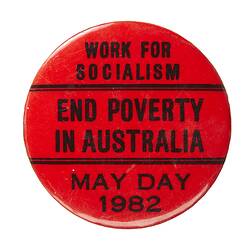

The Politics & Protest Badge Collection encompasses over 1,000 objects spanning the 20th century, with just a few examples dating from the late 19th century. The majority of pre-1950 badges belong to trade unions, clubs, societies and they generally identify membership as well as various campaigns. The range is astounding: seamen, nurses, hospital employees, transport workers, bricklayers, plumbers, firefighters and many more. In the second half of the 20th century, buttons tend to reflect the large-scale protest movements that took place, especially around sexual politics, nuclear power and the environment, the war in Vietnam and Indigenous land rights. The collection loosely traces the development of Socialism from what is known as the Old Left to the New Left. The early leftist movement involved blue-collar workers organizing themselves in a unionized structure to campaign along economic dimensions: wages, workplace safety and welfare. In contrast, the rank and file of the New Left was the highly educated youth protesting for social justice. There was a new-found radicalism and a belief in direct action, advocating the use of public strikes over negotiations. The collection illustrates this shift from the unionized movement to the decentralised radical protest. While most of early buttons represent movements clearly structured around organisations, buttons made post-1950 tend to represent campaigns instead of groups and the language employed shifts towards a much more radical tone.

Overall, the main purpose of pins is to advertise collective demands, desires and beliefs. However, during times of heated political debates they became a mechanism of identity formation. An oral history account from the 70s remarked how attending protests was, at the end of the day, 'a terribly social thing' (Pressley, 2002). Protestors could disseminate their views and at the same time create a collective experience. The Protest and Politics collection only includes objects that were made, used and collected in Victoria. The badges are symbols of their era, epitomizing the rhetoric and visual identity of the Australian political protest movement in the 20th century.

Reference list

Atwood, P. (2004) Badges. London: The British Museum.

McIntyre, I. (2009) How to make trouble and influence people: pranks, hoaxes, graffiti & political mischief-making from across Australia. Carlton, Vic: Breakdown Press

Pressley, A. (2002) Living in the 70s: Being young in Australia in an extraordinary decade. Random House Australia

More Information

-

Keywords

Political Protests, Public Protests, Socialism, Trade Unions

-

Authors

-

Article types

![Badge - [New Zealand Peace Badge]](/content/media/11/914011-thumbnail.jpg)

![Badge - [Hand holding Wheat]](/content/media/3/914003-thumbnail.jpg)