Overview

The Long Room provided from 1998-2015 a dramatic backdrop for the stylistic recreation of an enormous ship structure. The ship contained a series of set piece environments through which visitors could walk and become immersed in changing forms of shipboard travel over time. These included a 1850s clipper sailing ship, an early 1900s steamship salon, and a third class ocean liner cabin from the 1950s. These rooms evoked the conditions of the eras, including an evocative series of soundscapes, as well as featured a selection of collection objects.

Visitors were challenged to consider how technology has changed over time from a sea voyage lasting up to three months to a short 24 hour plane flight. The interactive included a contemporary refugee boat journey.

Migrant Transport Over Time

The Era of Clippers

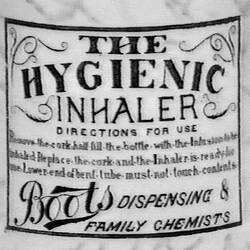

Complete dependence upon the winds meant that sailing from England or Europe to Australia might take up to four months, but a well-run clipper could cut this time almost in half. Clippers represented the pinnacle of sailing ship technology. With their streamlined hulls and acres of sail, designed to catch even the slightest breeze, they were built primarily for speed. Despite these improvements, however, clippers were often little better in passenger comfort below deck than the sailing ships of a century before. For 'steerage' passengers, conditions in cramped and unhygienic quarters became worse when tremendous storms were encountered in the Southern Ocean. At such times passengers were confined below deck for days, sick, torn and tossed, fearing for their lives. Although sadly common, a death at sea was still a terrible shock for passengers and crew alike. For the burial, the body was sewn into a piece of canvas or placed in a rough coffin (often hastily knocked up by the ship's carpenter) and weighed down with pig iron or lead to help it sink.

Driven by Steam

Although steam was initially slower than sail power, a sailing ship could make no headway without wind. The clever combination of steam and sails resulted in auxiliary steamers that could offer more predictable and dependable travelling times than sailing ships. The change from traditional wooden hulls to iron hulls enabled steamships to be larger and stronger, with increased space below deck. These new steamers offered greater passenger comfort, including grand saloons for first-class passengers and small cabins rather than open sleeping berths in steerage class.

Towards the end of the 1860s two major changes occurred in sea travel to Australia: the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the introduction of compound steam engines. Voyages to Australia entirely under steam power became practical, but it was the subsidy offered by a government mail contract that actually made the service profitable. Following the First World War, passenger shipping was further transformed by the introduction of steam turbines, cleaner oil-fired boilers and, later, the first diesel-powered motor vessels. Many passenger ships in this era also carried cargo to remain profitable, leading to compromises in passenger comfort, particularly in third class. By the 1930s, the leading shipping lines had begun introducing a new class of massive 20,000-ton ocean liners, setting unprecedented standards of luxury and elegance.

Troopships to Migrant Liners

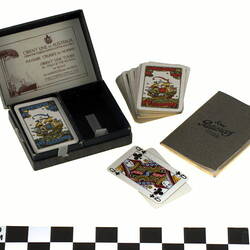

During the Second World War migrant ships were redeployed to war service as armed cruisers, floating hospitals and troopships. After the war, many ships that had carried soldiers were hastily converted to meet an urgent demand for migrant transportation. Passenger comforts on such troopships were very limited. Accommodation on these vessels was extremely basic, with large empty holds fitted out with double- or triple-tiered bunks; the food was plain and sometimes inadequate; overcrowding was a common complaint; and all passengers, including families, were split into men's and women's quarters. As the number of post-war migrants - as well as tourists and business travellers - increased, shipping lines realised the potential profits to be made. A more competitive market rapidly developed after 1948. New purpose-built migrant liners were introduced, and a new approach was taken to attracting immigrant trade. The signature large dorms of the early post-war period were replaced with cabins, which in some cases were air-conditioned; daily newsletters, port-of-call booklets and decorative menus were designed; balls, parties and sporting competitions were arranged; and children were better catered for, with playrooms and organised deck games. Souvenir shops were also installed on ships of this era. This was clever marketing and it increased companies' revenue. Souvenirs included postcards, sailor dolls, ashtrays, cocktail swivel sticks and spoons, all sporting the ship's name.

Related Collection Objects

The Museum holds a rich collection of objects, documents and images relating to migrant transport over time. This includes ship and aeroplane models, shipboard diaries, shipboard souvenirs, newsletters, menus, programs etc distributed by shipping companies, luggage, tickets of passage, etc. The journey made by migrants to Australia remains an enduring memory for people.

- SS Orient Steam Ship Model, 1879

- Jervis Bay Steam Ship Model, circa 1921

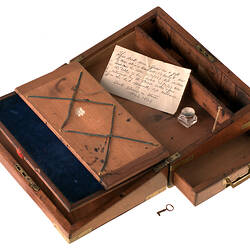

- Diary written by Ally Heathcote on the SS Northumberland, England to Melbourne in 1874

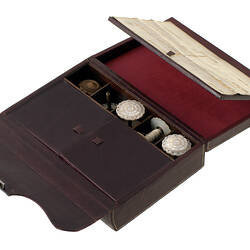

- Jack Rasmussen's cut throat razor, a souvenir for crossing the equator in 1921

- Trunks and suitcases

- Qantas Lockheed Super Constellation Aeroplane Model

- Navigational equiptment including sextants and telescopes

More Information

-

Keywords

Museum Victoria Exhibitions, Immigration Selection, Assisted Immigration, Immigration Policies, Immigration Debates, Immigration, Immigration Voyages, Migration & Settlement

-

Authors

-

Article types